For Upcoming 2020 Arts & Culture Calendar or email giac05@icloud.com to get listing in advance

Mahalo to all who enjoy and support Art and Culture on Kaua’i

Donate by clicking here

Register on AmazonSmile.Org & select Garden island Arts Council to receive .05% of your eligible purchases

Click here for the link to EKK on Facebook

Who’s Coming Next Week? Monday, February 17

A Mesmerizing Jaunt through the Evolution of Hula

Michael Pili Pang and the dancers of Halau Hula Ka No’eau Hula Academy held the audience captive as they chanted, danced and told the story of hula as it reflected the life and times of the people of Hawai’i. They were the very embodiment of the EKK 2020 theme – “Mele, Hula & Mo’olelo.” Pili Pang seeks to train dancers to be “smart” rather than only pretty and his touring dancers are exactly that.

The first hour was fun for the ‘ukulele circle with Paul Kim and Henry Barrett teaching two songs to the ‘ukulele circle while Michael Pili Pang and his dancers taught a Pa’i Lima (hand clapping) hula to the rest of the audience. The rapid finger motions describing the phases of the moon were really tricky for most but at least we all clapped in unison when it got to the chorus. Kids and sign language speakers picked it up faster. In fact, young Kamaha’o Haumea-Thronas, sitting in front of me, was dancing with his fingers…no problem. As soon as Michael finished his lesson, Kamaha’o picked up his ‘ukulele and raced over to the ‘ukulele circle to learn the songs. Next time I looked up, he was standing with Paul and Henry singing Ka Uluwehi O Ke Kai. Great to see someone taking it all in.

Kawailana, skillfully beating the pahu drum, opened the program chanting the Oli Aloha to welcome everyone. A typical hula protocol asking for permission to enter our space was demonstrated with the chanting of Kunihi Ka Mauna and Oli Komo. Five dancers entered from the back of the auditorium chanting and walking up to the stage.

The audience sat transfixed as Pili Pang shared the story of the origin of hula which started on Kaua’i at the Ke Ahu A Laka Keahualaka hula mound on the slopes of Ke’e Beach in Ha’ena with the Godly encounters between Madame Pele, her “human” boy toy Lo’hiau, and Pele’s younger sister, the Goddess Hi’iaka. The first half of the performance was a fascinating revelation of the encounters between Gods and mortals as they acted out their emotions of love, passion, jealousy, anger and revenge.

The chanting by Kawailana Pascual was superb, the dancers were top notch and MPP’s narration, often humorous and at times irreverent, guided us through the passionate interactions of the principal players in the hula drama. The “voices” MPP used in conveying the thoughts and actions of Pele and Hi’iaka gave us a present-day context to understand their desires, intentions and actions as he used today’s every-day language to convey their thoughts and actions.

Just as the hula dancers asked permission to enter our space, the legend speaks of a stranger to Kaua’i asking for permission to cross the Wailua River. After being ignored repeatedly, she vehemently persisted and was finally acknowledged and granted access, “She’s from the Pele family…hot tempered people … let her pass!” Thus, Pele gained access to Ke’e beach where she first set eyes on the beautiful Lohi’au. Ka Poli Laua’e danced by the five dancers to Kawailana’s powerful chanting told this story of the love affair between the Goddess Pele and the mortal Lohi’au. Being in spirit form, she could not touch Lohi’au, so she went back to Hawai’i Island to get her younger sister Hi’iaka to return to Kaua’i to fetch the handsome Lohi’au. “I will have him for the first three nights and then you can have him after that,” offers Pele. Hi’iaka agrees.

The youthful Hi’iaka embarks on her island-hopping journey to do her older sister’s bidding, but finds that she arrived too late because the foolish, Lohi’au, so love-sick with the dream-like image of Pele, hanged himself in his grief. Hi’iaka, being a goddess, had the power to bring Lohi’au back to life by performing Ahi Lele (flying fire) by burning the branches of the Papala tree and catching Lohi’au’s spirit and capturing it in a coconut shell. Ke Ahi Malie, a guttural chant with a unique drumming style and rapid uhe beat steps which originated on Kaua’i, coupled with swift hand and body motion represented the powerful images of the flying fire ceremony performed by Hi’iaka.

Because the fire magic ceremony would take Hi’iaka several weeks to complete, they danced 13 chants as a distraction; the dancers did one of the 13 chants to Huli Ke Ao. Hi’iaka successfully restores the mortal Lohi’au to life. She is stunned by his beauty but remembers that Pele had cautioned her not to touch him until after she had spent the first three nights with Lohi’au. After that, he was hers. Hi’iaka had agreed to the arrangement provided Pele looked after her Lehua forest on the Eastside of the volcano and be sure no lava destroyed her forest.

Halau Hanalei, a chant that describes the torrential Hanalei rains that occurs infrequently on the north shore like the one that caused much destruction in 2018, describes the conflicting emotions that Hi’iaka is experiencing, wanting to help Pele to get Lohi’au and experiencing her own arousal for Lohi’au.

Having left Hawai’i Island as a youth, Hi’iaka was now a young woman experiencing womanly desires for this beautiful man that she has brought back to life. As she prepares for her journey to cross the Ka‘ie’ie Channel between Kaua’i and O’ahu, she experiences ho’ailona, the symbolism or thought in the form of a dream that her friend Hopoi is trying to escape from the lava flow by climbing the trees, together with the sound of gravel-like chattering gossip which convinces her that older sister Pele has not kept her promise to protect Hi’iaka’s Lehua Grove. Embarking on the two-person voyage in the canoe to the chant No Luna I Ka Hale Kai, Michael asked the audience to imagine “what’s going to happen?” with Hi’iaka and Lohi’au alone in the canoe.

Hi’iaka finally arrives on Hawai’i Island with Lohi’au and encounters her sister Pele with “You let go of my Lehua trees, so I am going to hug your husband and give him a big kiss!” The ensuing battle between Pele and Hi’iaka was so fierce, raging from the crescent of the volcano down to the plains of Puna; Aia La ‘O Pele chant describes how the heavens lit up with fires that went higher and higher and could even be seen from the island of Maui.

So fierce and long was the battle between the two sisters that the Gods had to stop the fighting before they reached the water table as that would destroy everything. Sadly, Lohi’au is the casualty of the battle. The fascinating saga of the romance triangle as it was depicted in chants, kahiko hula and mo’olelo could not have been told with any more clarity.

Surprises at EKK are common occurrences as we are often treated to unplanned happenings but tonight pulled the plug out from under me. Michael called me up to the stage to help him and proceeded to read a letter from Kahu Kenneth Makuakane, a frequent presenter at EKK and currently the chair of the “Lifetime Achievement Industry Award” selection committee for the Hawai’i Academy of Recording Artists. (see attached letter at the end of this wrap.) Michael announced to an ecstatic EKK audience that EKK would be the recipient of the “Lifetime Achievement Award” in 2020. The Halau dancers ended the first half of the program with the powerful Hula Ma’i (procreation chant) He Ma’i No ‘Iolani which Michael stated would be appropriate to see that EKK enjoys continued procreation.

If the powerful hula kahiko first half kept everyone captive, the light and colorful second half of hula ‘auana was both entertaining and instructive as Michael narrated in English the lyrics of the Hawaiian mele; understanding the fluid moves of the hula choreography became so clear. It was simply wonderful! The stories of the life and times of the people of Hawai’i are captured in hula and chants, but it is not a static thing that sits on the shelf. Rather it evolves with the life and times of the people who create the music and the dance.

With the advent of the missionaries and the practices imposed by them onto the Hawaiians, such as teaching them to sing Hymns so they could go to heaven, the music by the Hawaiians changed. Their new topics of dance were the whaling ships, social dancing, people and Hawaiian royalty rather than Gods and Goddesses. The Hawaiians began to sew together their dances into Hula Ku’i, which mean to sew together the stories. Two such Hula Ku’i songs danced in the modern style followed.

Ku’u Mai Balota is about the “Ballot” for the first election of Lunalilo in which not everyone was allowed to vote. Michael did the chanting in a guttural style while his three male dancers did a brisk side-kicking hula. Aia Moloka’i Ku’u Iwa with two male dancers and a female dancer was a playful and charming dance about a love triangle on the cliffs of Kalaupapa. The dance alluded to the piecing winds and swordfish stabbing the heart as the two suitors vied for the affection of the beautiful lady. ‘Auana translates to “wandering away” perhaps from working on tasks which did not sit well with the plantation owners and the missionaries, so in 1850, a LAW was passed saying that outside of the two ports in Lahaina and O’ahu there was to be no “congregating” and no, there was to be no hula.

In 1893, Hawai’i was taken over by the Americans. Earlier, every Hawaiian could read and write and enjoyed free education and free health. But at the turn of the century, they were forbidden to speak Hawaiian in public. Hula changed. Music changed. The Hawaiian people changed.

King Kalakaua was the only world ruler who circumnavigated the globe. As he traveled, he saw that all countries had national dances and Hawai’i had none, so he got rid of the law of 1850 that forbade the dancing of hula and reinstated hula as the national dance for Hawai’i, leaving the legacy of the Merrie Monarch hula festival.

Maile Lei by Maddy Lam was written for the Firestone Convention in November 1963. It was the day that John F. Kennedy was shot. The Convention did not happen but the song became a tribute to JKF. The three dancers in long white holoku wearing long strands of brilliant purple leis and green maile leis were visions of beauty and elegance as they danced Maile Lei in the modern ‘auana style. Another Maddy Lam song written together with Mary Kawena Pukui, He Aloha Ku’u Ipo, is a simple song of love. Love affairs and stories that touch people’s hearts were popular in the 60’s and 70’s.

Many songs are written about or for the royalty. The mele titled Ka ‘Ulu Ali’i Ni’ihau E hula for Queen Kapi’olani, daughter of King Kaumuali’i of Kaua’i, tells about her visit to Ni’ihau, the secret pao’o water from the fresh-water spring which bubbled out of the hidden clefts in the rock, the sideward-growing sugar cane buried in the sand dunes, and the sacred ‘ulu or breadfruit tree which is planted in a reef hole thirty feet below the ground so the fruit was easily picked at ground level.

Another hula ali’i was about King Kalakaua about his travels to the Himalayas. Ia ‘Oe E Ka La (You are the Heavenly Sun) was written by a relative about King David’s trip to the Himalayas warning the King to “tread lightly and be careful who you touch as you are our Monarch; be sure to take a sip from Wai’olu, the Fountain of Youth.”

Michael spent a lot of time at the home of his kumu hula Maiki Aiu Lake, wife of Kahauanu Lake, who wrote many songs with Mary Kawena Pukui. He observed that they often argued about how to sing a song. When Michael asked him how they resolved that, Kahauanuu replied, “I married her.” Pua Lililehua is one such song for which there is a play on words; it also means “to be jealous.”

To show that tourism was definitely a part of Honolulu, three male dancers looking youthful and spiffy in white pedal pushers and green & yellow aloha shirts danced the energetic Aloha Tower hula. Michael pointed out that because all of Honolulu set their time by the clock on Aloha Tower, when their clock was off, so was everybody else’s in Honolulu. Perhaps that was the start of “Hawaiian Time”.

Waikiki means “spouting water” because the water from Manoa flowed down to Waikiki and bubbled up all over Waikiki; salt water ponds all over Waikiki were covered with fragrant Lipoa seaweeds. Once the area where royalty built their “country homes,” Waikiki soon became the tourist hotspot. Waikiki Hula was written for Pualeilani, the Waikiki Home of Prince Jonah Kuhio Kalaniana’ole. It was given to Helen Ayat by her mother, a lady-in-waiting to Princess Kahanu, wife of Prince Kuhio.

Hapa haole music was first introduced by a group of NY City folks in 1910. When they saw how popular Hawaiian music was at the Pan Pacific Festivals in San Francisco featuring pineapple, sugar cane and hula dancers, these enterprising songwriters who had never been to Hawai’i started selling music sheets with hapa-haole songs and became instant millionaires. Hawaiians caught on quickly and started writing their own hapa-haole songs; these songs defined a distinct period in Hawaiian music. Sunny Cunha’s Hapa Haole Medley showed off the sweet charm and expression of a happy lighthearted period in Hawai’i. The couples dance with the hula girl shaking her uli uli, wearing cellophane hula skirts and plumeria headbands so typical of that period, was so charming.

R. Alex Anderson, who lived to be 101 years old, every day wrote a song and placed it in his piano bench. One of his best known songs is the popular Mele Kalikimaka, which is sung worldwide. He also wrote the Punahou School Alma Mater. Dressed in a long flowered holoku, beautiful Kaleo danced another one of his popular hula songs, Lovely Hula Hands. (That was my first hula taught by my kumu hula Helen Kekua.) Three dancers dressed in the long flowered holoku danced Michael’s favorite hula classic, Misty Rains and Lehua (Forever in Love), composed by Kahauanu Lake. These descriptive hula tell stories via dance and are very much a part of Maiki Aiu Lake’s hula style. She started teaching hula at the tender age of 14.

Maiki Aiu Lake, who could not write Hawaiian, got her Uncle Claude Malani to help her write Aloha Kaua’i in the 1950’s as a thank you song to the people of Kaua’i who had sent her dancers back to Honolulu with a huge box of maile leis when they performed on Kaua’i. Michael’s amazing “smart” halau dancers – Deborah Ing, Kathryn Kamealoha, Tammi Silva, Kai Paiva, Hokuloa Fortuna and Kawailani Pascual – danced this hula favorite. Joining the hula team for this final hula were Kaua’i dancers Po’ai Galindo, Vern Kauani, Mahina Baliaris and Sabra Kauka.

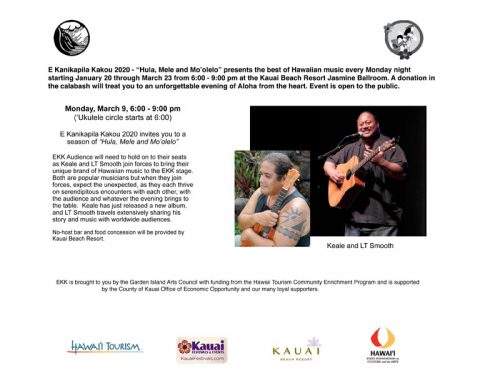

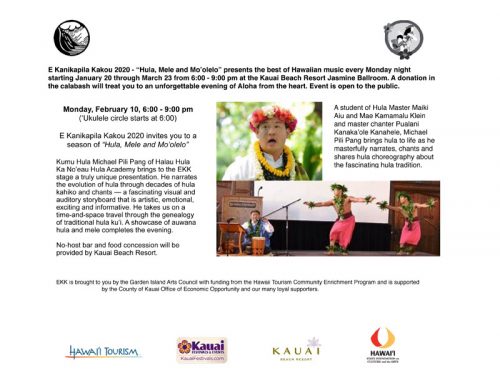

A student of hula master Maiki Aiu Lake, Mae Kamamalu Klein and master chanter Pualani Kanaka’ole Kanahele, Michael brought the fascinating hula tradition to life as he masterfully chanted, narrated, and translated the lyrics of the mele so that even the novice could understand the meaning of the hula movements. The entire evening was a fascinating visual and auditory storyboard that was artistic, emotional, exciting and informative. He took us on a time-and-space travel through the genealogy of traditional hula ku’i.

Mahalo Michael Pili Pang!

# # # # #

If you have a disability and need assistance for Monday events, email Garden Island Arts Council at giac05@icloud.com.

Info at www.gardenislandarts.org — “Celebrating 43 years of bringing ARTS to the people and people to the ARTS”

Funding for E Kanikapila Kakou 2020 Hawaiian Music Program is made possible by Hawai’i Tourism through the Community Enrichment Program, with support from the County of Kaua’i Office of Economic Development, the Garden Island Arts Council supporters and the Kaua’i Beach Resort. Garden Island Arts Council programs are supported in part by the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts through appropriations from the Hawai’i State Legislature and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Leave a Reply